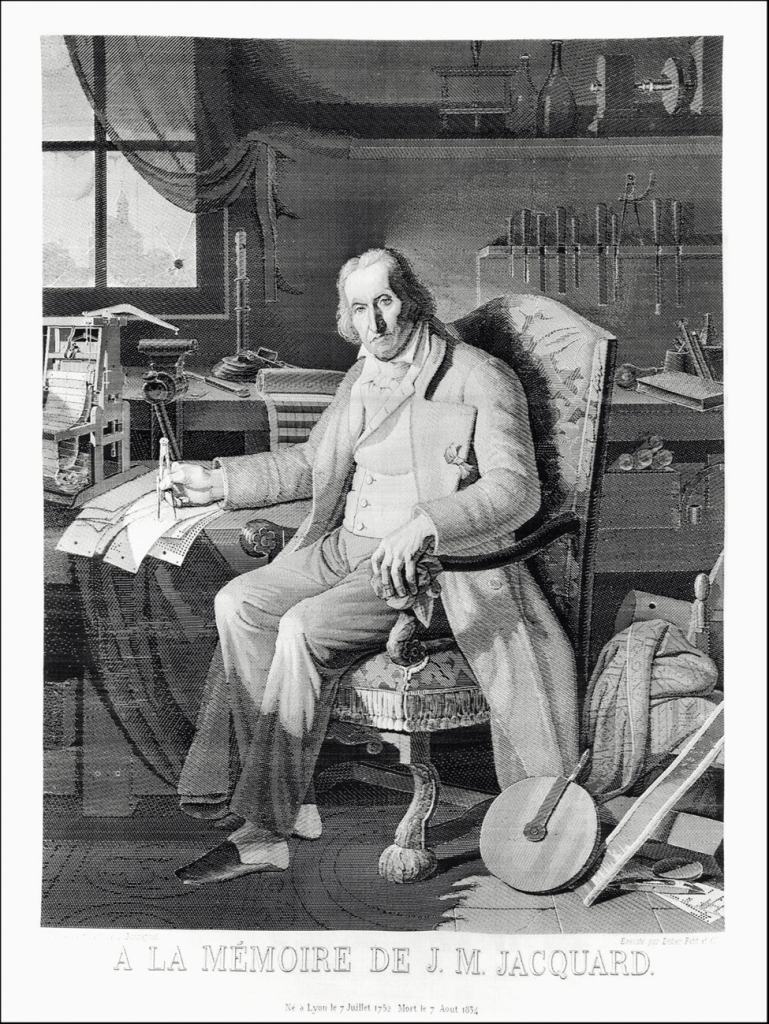

One evening in 1842, the Duke of Wellington and Prince Albert, Queen Victoria’s husband, attended a soirée at the house of British scientist and mathematician, Charles Babbage. Babbage was delighted to show them his newest exhibit: the portrait of a French inventor named Joseph-Marie Jacquard, who had died six years earlier (August 7, 1834). The portrait shows Jacquard sitting on a cushioned chair at his workbench. He is holding a pair of calipers against long strips of cardboard with tiny holes punched on them. Behind him, various tools hang on the wall and rolled plans are sticking out of a drawer. His clothes and thoughtful face suggest a successful and prosperous man.

Babbage’s guests thought the portrait was an engraving. However, it was a piece of woven silk, originally painted by Lyons artist Claude Bonnefond, and woven by Didier Petit & Co. in 1838. The portrait was an illustration of the capabilities of Jacquard’s loom. Jacquard’s invention was the world’s first automatic machine for weaving elaborate images. This portrait was a rather small 14″x20” picture and contained 24,000 rows of weaving. A programming device called a punched card controlled each row. These punched cards held the secret to Jacquard’s automatic loom that weaved complex patterns and images. Jacquard’s small picture was an example of a technology that would transform our world and lead to the information revolution.

Jacquard’s invention

A loom is a machine that weaves cloth by interlacing two or more strands of yarn at right angles. To create a simple pattern, a weaver raises a set of stationary parallel threads (wrap) so that another set of threads (weft) interlaces with this wrap. This type of loom was suitable for weaving only plain and undecorated cloth. The first loom that created complex patterns was the draw loom because it allowed individual or group wrap threads to be manipulated to create a pattern. The problem with this type of loom was that the weaver had to operate the shuttle and the draw-boy had to stand atop the loom to raise and lower the warp. This was time and labor intensive. Even the most skilled weaver could only weave a couple of rows (picks) of cloth in one minute.

Because the draw loom was so slow and tedious, Jacquard, son of a master silk-weaver, was inspired to invent something better: a faster loom capable of being programmed to weave decorative and complex designs. In 1789, the French revolution interrupted his work to fight in the defense of his hometown Lyons. After the war, he continued his work and in 1804, he perfected his loom design with an innovative punch-card system that controlled individual warp threads. A hole on the card meant that a rod would pass through it and activate a hook to lift its wrap thread so that the weft thread could pass under. No hole meant that the rod would rest against the card.

The Jacquard loom was automatic, flexible and rapid. When using this loom, the weaver did not need an assistant. Instead, the weaver could control and operate the loom alone. Above all, the loom could reproduce and replicate any pattern a designer could think of. The designer would paint an image on squared paper. Then, a card maker would translate it onto punch cards, and a weaver would convert it into cloth. An astonishing fact about the loom was its speed. It could weave twenty-four times faster than the draw loom. In the past, a weaver would produce only a couple of picks of cloth per minute. Now he could weave about forty-eight picks per minute. A skilled weaver could produce two feet of silk cloth per day in comparison to one inch of silk cloth per day using a draw loom.

Jacquard’s invention impressed Napoleon so much that in 1805, he declared the loom public property. He awarded Jacquard a lifetime pension and royalties per loom in France for six years.

Applications beyond textiles

Jacquard’s mechanism found applications far beyond silk weaving. In 1836, Charles Babbage used the punch-card system to guide cogwheels, instead of threads, to program a mathematical calculator that he called the Analytical Engine. This engine is considered to be a Victorian computer. As technology advanced, new inventors were fortunate to employ the steam engine and, later, electricity to power their looms. In the U.S., statistician Herman Hollerith used Jacquard’s punch-card system to build a machine that tabulated the results of the 1890 census. The holes on the cards told Hollerith’s machine to “weave” data instead of threads. Punch-card technology operated electronic computers until the invention of digital input in the mid-20th century.

References

Essinger, J. (2004). Jacquard’s Web: How a Hand Loom Led to the Birth of the Information Age. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hodakel, B. (2021, June 21). What is Jacquard fabric: Properties, how its made and where. Sewport. Retrieved September 15, 2022, from https://sewport.com/fabrics-directory/jacquard-fabric

Programming patterns: The story of the jacquard loom. Science and Industry Museum. (2019, June 25). Retrieved September 15, 2022, from https://www.scienceandindustrymuseum.org.uk/objects-and-stories/jacquard-loom

Smith, S. (2015, October 22). He Wove The Future With His Punch Cards. Investors Business Daily, A03.