Embroideries were part of every bride’s dowry she installed in her new home. At the same time, she transferred her embroidery designs and techniques to her husband’s homeland. The custom of making a dowry was common in Greece. Women wove cotton, linen, and silk, creating household items such as bedspreads, aprons, towels, pillowcases, and valances. They used them in domestic life and in both religious, and civil ceremonies. The scenes depicted on these two 18th-century rectangular cushion covers exhibited at the Benaki Museum are examples of wedding textiles and reveal the influence of Ottoman culture on Epirus society.

The bridal cushion below from Ioannina depicts the bride with two other figures by her side. It was donated to the museum by Alexandra Choremi-Benaki (1871-1941). The second cover right depicts a bride on horseback accompanied by two horsemen. Helen Stathatos (1887-1982) donated it to the museum as part of her extensive collection of Greek art, which spanned from the Bronze Age to the nineteenth century and included jewelry, embroideries, textiles, and manuscripts. Both cushions have a rich narrative element with motifs that reflect the influence of the Ottoman character in 18th-century Greece fused with the local traditions of the Epirus region.

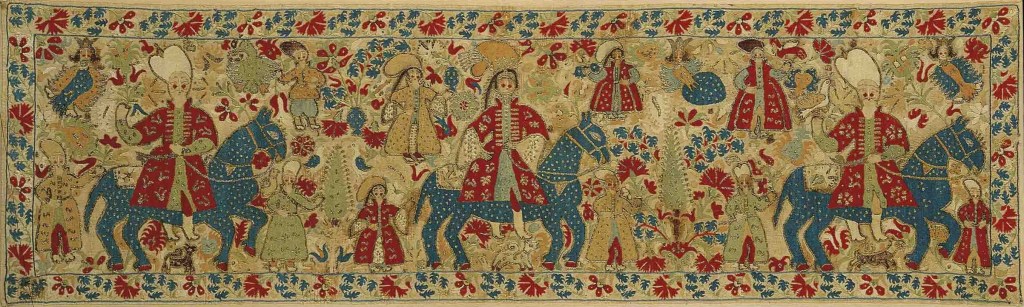

Bridal cushion depicting the mounted procession of the groom and the bride and her parents standing in the centre. Ioannina, Epirus, 18th century.

The Ottomans conquered Epirus from the end of the 15th to the 19th century and turned Ioannina into a textile centre of commercial embroideries. When Ali Pasa of Tepeleni ruled the region in the 18th

century, he made Ioannina the greatest and most influential city in Greece. Ioannina produced embroidered dresses and uniforms on an industrial scale for the Ottoman officials and the Balkans. The Ottoman style of life became so integral that embroidered textiles became a part of the

Greek domestic environment. The Greeks of Ioannina adapted not only the Ottoman dress but also similar interior decorations for their houses.

A Greek song says, “Beautiful is our bride, beautiful is her dowry.” This set of lavish cushions forms part of a bride’s dowry, which she spent much time embroidering for her special day. They are heavily decorated with motifs and stitches that shed an insight into cultural exchanges and what a marriage procession might have looked like. The cushion below features the procession of the bride to the church. The bride must be young, as indicated by her petite figure. Traditionally, the bride’s father and brother escort her to the church, followed by a crowd of relatives and guests. Here, the bride is escorted by her parents and two men on horseback.

Bridal bolster depicting a wedding scene. Silk embroidery on linen. Ioannina, Epirus, 17th-18th century. Courtesy Benaki Museum.

All human figures are dressed in lavish Ottoman costumes, from headdresses to boots. The men wear (turbans), overcoats with several button closures, trousers, and boots. The two horsemen sit on

embroidered blankets on the backs of the horses. The women also wear similar overcoats with long wide sleeves. The bride’s headdress is an impressive crown with a hairpin that resembles a tree branch.

Such hairpins are found in 16th-century engravings and 19th-century Macedonian costume. This hairpin symbolises the transition from childhood to adulthood and married life. (see Benaki Museum close-ups). In other versions of wedding embroideries, the bride’s mother wears such a hairpin, too.

Two ovoid-shaped water ewers stand on either side of the bride’s parents. Women used such ewers to carry water from the village’s spring to their houses for cooking, washing, and cleaning. The ewer on the right is shaped with a curved spout, similar to the Ottoman style. Both ewers are filled with blue hyacinths, red carnations, pomegranates, and white tulips. These flowers were characteristic of an Ottoman Iznik pottery, famous for its intricate designs, such as flowers, geometric patterns, and calligraphy. It applied vivid colours, including cobalt blue, turquoise, deep red, and emerald green.

The ewer on the left includes two figures with a bird body, human legs in boots, and a woman’s head, perhaps a creature from Greek mythology. Birds are present in wedding rituals and represent freedom, good blessings, unity, and a new beginning for a married couple. The cushion’s background includes many flowers, birds, and dogs expressing a sense of euphoria. It seems as if all nature’s creatures celebrate the joyous event.

Both cushions are embroidered with running, split, and herringbone stitches. The running stitch is used in diagonal alignment to fill motifs, creating a smooth satin surface. The split stitch is used as a stem stitch

and to outline borders. The herringbone stitch contrasts with the other stitches due to the interlacing of the thread. This stitch adorns serrated leaves, flower petals, and the button closures.

The narrative scenes on the cushion below apply similar figures, motifs, and embroidery techniques. This version features the bride mounted on a horse and two horsemen on either side. Perhaps, the horsemen escort the bride to her new home. The crowd of relatives and guests, featured on a smaller scale, follows the wedding procession. Again, all human figures are dressed in Ottoman fashion. The bride wears a turban with a jewelled crown and a fancy hairpin on top. The same bird-like creatures, dogs, and flowers decorate the background. The horseman on the right seems to hold a partridge on his right hand. The partridge is associated with marriage. It personifies the bride’s feminine energy and fertility. These bridal cushions depict an impressive wedding procession of a wealthy local family. All human figures on the cushion are dressed in luxurious Ottoman costume. These cushions are remarkable examples of rich artistic and cultural traditions that emphasize both the Greek native and Ottoman values.